Beyond Transactions: A Real Estate Professional’s Role in Complex Family and Aging-Related Decisions

When Aging, Assets, and Reality No Longer Align

A Professional Commitment to Navigating Dementia, Family Deadlock, and Complex Real Estate Decisions

Real estate is often described as a business of numbers, markets, and timing. In reality, some of the most consequential moments in this profession unfold far from spreadsheets and comparable sales. They unfold in living rooms, hospital corridors, and family conversations shaped by aging, illness, fear, and responsibility.

I was recently confronted, in a professional capacity, with a situation that brought this reality into sharp focus. It involved an elderly gentleman diagnosed with dementia, his adult children, and an ailing spouse whose medical and daily-care needs had reached a critical point. This was not a family lacking resources. On the contrary, it was a wealthy family with multiple real estate assets spread across several countries, accumulated over decades and governed by different legal, fiscal, and cultural frameworks.

From a purely financial and transactional standpoint, the solution was clear.

The means existed.

The assets were available.

Market conditions were workable.

To provide appropriate care and preserve safety and dignity, liquidating part of the family’s real estate portfolio was both feasible and responsible.

And yet, the situation was entirely immobilized.

The patriarch refused to acknowledge the reality of the circumstances. He rejected the sale of property, resisted professional care, and viewed any discussion involving assets with deep suspicion—particularly when initiated by his own children. What appeared externally as obstinacy or control was, upon closer examination, something far more complex and far more consequential.

This was not a negotiation problem.

It was not a pricing issue.

It was not a lack of sophistication or understanding of value.

It was a collision between cognitive decline, identity, and control.

In families of substantial means, this collision is often misunderstood. There is an assumption—shared by outsiders and sometimes by the families themselves—that wealth creates flexibility and solutions. Research shows the opposite can be true. Wealth does not protect against late-life cognitive distortion. In some cases, it intensifies it, particularly when assets represent legacy, authority, and permanence.

At that point, stepping away would have been easy. But when real estate becomes the mechanism through which care, safety, and dignity must be funded, professionalism demands more than execution. It demands understanding.

That conviction led me to undertake a deep examination of the medical, psychological, and academic literature surrounding dementia, late-life financial paranoia, and decision-making impairment. This was not academic curiosity. It was applied research, undertaken with the explicit purpose of helping a family navigate a situation that could not be resolved through conventional transactional tools.

What the research reveals is sobering—and it explains why families with extensive assets, international portfolios, and sophisticated advisors can still find themselves completely paralyzed.

Geriatric psychology and psychiatry describe a phenomenon commonly referred to as late-life financial paranoia, frequently associated with dementia and late-onset neurocognitive disorders. Individuals affected may retain articulate speech, long-term memory, and familiarity with past business dealings—including complex real estate structures—while simultaneously losing the executive capacity required to evaluate risk, integrate new information, and adapt to changing realities.

This distinction is critical.

The issue is not ignorance.

It is not lack of experience.

It is decision-specific cognitive impairment.

Research consistently shows that dementia does not dull emotional response. In many cases, it intensifies fear. As cognitive flexibility erodes, ambiguity becomes intolerable. Control becomes central. Financial decisions—particularly those involving asset liquidation—are no longer evaluated logically. They are experienced as existential threats.

In this context, real estate assumes an outsized psychological role. Property is not merely an asset class. For many aging patriarchs—especially those who built wealth across borders and decades—it represents identity, authority, permanence, and proof of a lifetime’s work. Selling property late in life can feel like erasure: not a transaction, but a loss of self.

The multinational nature of such portfolios often compounds the problem. Assets spread across jurisdictions can reinforce a sense of control during healthy years, yet become overwhelming and threatening once cognitive decline sets in. The very complexity that once symbolized success can later amplify fear and rigidity.

The literature further demonstrates that this dynamic frequently leads to family alienation. Adult children attempting to act responsibly—to fund care, reduce risk, or prevent collapse—are often reinterpreted as adversaries. In wealthy families, this suspicion can be magnified by longstanding power dynamics, inheritance anxiety, and the symbolic weight of legacy assets.

Crucially, clinical research is clear: family conflict in these cases is usually a symptom rather than a cause. Attempts to reason, persuade, or apply pressure—especially around property—tend to reinforce fear rather than resolve it. Logic fails not because it is flawed, but because it is no longer the governing system.

Cultural and historical factors can further intensify this pattern. Studies of immigrant and internationally mobile families show that early-life instability, displacement, or exposure to asset loss can resurface in old age as extreme fear of financial erosion. Even decades of success do not erase this imprint; they suppress it until aging removes the psychological structures that once maintained control.

As the research deepened, another difficult reality became unavoidable. Despite medical recognition of cognitive decline, the only formal mechanism capable of breaking the deadlock was a legal one: a declaration of incapacity.

In theory, this process exists to protect vulnerable individuals and those who depend on them. In practice, it introduces a new and often harsher reality—particularly in cases involving significant, multinational assets. Once a patriarch is legally declared incompetent, decision-making authority does not automatically pass to the family or adult children. Instead, it frequently shifts to the courts.

At that point, assets are no longer managed through family judgment or long-established intentions, but through judicial oversight, procedural timelines, and court-appointed structures that may or may not reflect the family’s history, values, or priorities. In cross-border situations, this complexity multiplies, as different jurisdictions impose different standards, delays, and interpretations.

For the family involved, this was not merely a legal decision. It was a moral one.

The children understood that pursuing a declaration of incompetence could unlock practical solutions—but at the cost of publicly and legally defining their father by his decline rather than his lifetime of agency. They struggled with the idea of placing his autonomy into the hands of the court, knowing that doing so would fundamentally alter the family dynamic and remove decisions from their stewardship.

Ultimately, they could not bring themselves to take that step.

This hesitation is neither uncommon nor irrational. Research and clinical literature consistently show that families often delay or avoid formal legal intervention not because they deny reality, but because the emotional and ethical weight of defying a parent—particularly one who built the family’s wealth and identity—is immense. The law may offer structure, but it does not resolve grief, loyalty, or moral conflict.

In this particular case, the research proved consequential in another way. Once the family understood that they were dealing not with stubbornness or willful obstruction, but with a recognized neurocognitive pattern, the framing changed. The focus moved away from arguing about property—despite its scale and international complexity—and toward seeking appropriate medical and geriatric support.

That shift allowed family members to pursue the right professional help to mitigate the situation, reduce immediate risk, and stabilize care—without forcing a legal rupture they were not emotionally prepared to create.

The real estate component did not disappear. But it could finally be approached within a framework grounded in cognitive reality rather than confrontation.

For real estate professionals, the implications are profound. As wealth becomes more global and populations age, we will increasingly encounter transactions blocked not by feasibility, but by fractured perception. Handling these situations ethically requires more than technical expertise. It requires the willingness to engage with complexity, to recognize the limits of logic, and to act with restraint when pressure would be easier.

The research I undertook did not produce an easy answer. What it produced was a framework—one that replaces frustration with understanding and urgency with care. It reinforced my belief that professionalism in real estate is not defined solely by outcomes, but by how we conduct ourselves when assets, aging, and human vulnerability collide.

Late-life financial paranoia, particularly when layered with dementia, transforms rational decisions into psychological battlegrounds. The refusal to sell property—even vast, international holdings—is rarely about greed. It is about fear, identity, and neurological change.

Recognizing that reality, and responding to it thoughtfully, is not outside the role of a real estate professional who handles complex transactions and difficult life situations.

It is central to it.

Closing

Situations like this are difficult precisely because they sit at the intersection of aging, wealth, family responsibility, and fractured reality. They are not solved by pressure, speed, or purely transactional thinking. They require patience, perspective, and an understanding of when real estate is no longer just about property, but about care, dignity, and risk mitigation.

If you are confronted with a similar dilemma—particularly one involving complex or international assets, aging family members, or decisions complicated by cognitive decline—and need thoughtful guidance grounded in professional experience and research, feel free to reach out.

You can contact me directly here:

Hashtags

#RealEstateProfessional #ComplexTransactions #GlobalRealEstate #WealthAndAging #HumanSideOfRealEstate #DementiaAwareness #ElderCare #EthicalAdvisory #ClientAdvocacy #ProfessionalCommitment #AgingAssetsReality #DementiaFamilyDecisions #RealEstateChallenges #ElderlyCare #FamilyWealthManagement #LegalFiscalFrameworks #ComplexFamilyDynamics #MedicalDecisions #AgingParents #EstatePlanning #FamilyDeadlock #ProfessionalCommitment #NavigatingComplexity #WealthManagementTrends #Eytan #Benzeno

Share This Post

💬 Join the Discussion

Have thoughts on this article? Share them below! Sign in with your GitHub account to leave a comment.

More Posts

View All Posts

Had You Heard of Notion? Have You Used It? It is the early shape of the cognitive work

Discover the true power of Notion as an all-in-one collaborative workspace platform. Learn how it revolutionizes knowled...

Mastering Your Sphere of Influence in Real Estate

When it comes to real estate success, the most powerful tool in your arsenal isn’t cold leads or expensive ads — it’s yo...

Low-Cost Strategies to Win Real Estate Listings: Proven Tactics That Actually Work

You don't need a massive marketing budget to secure quality listings. Learn proven low-cost tactics including the Magic ...

The Great Housing Reset: What 2026 Means for Buyers, Sellers, and Investors

2026 marks the beginning of a historic shift in real estate. After years of impossible affordability, the market is fina...

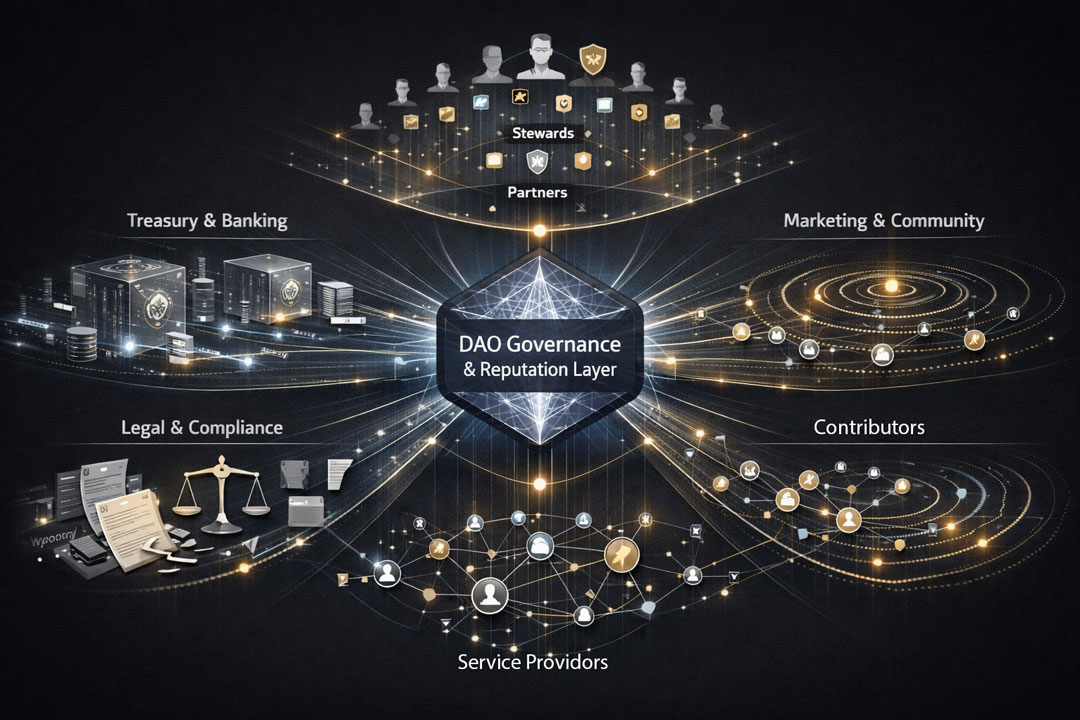

The Future of Work is Here: DAO-Firms and the Automation of Trust

Explore how DAO-Firms will reshape traditional companies in the future of work. Learn about the automation of trust and ...

The Rise of the AI University: A Bold Vision for $5K Learning

Discover the future of education with AI-driven, self-paced learning. Earn a fully accredited certification for just $5...